Exploration 1497-1615: Verrazzano, Hudson, Block

It is often speculated that Basque and English fishermen may have been landing on the coast of Labrador or Newfoundland as early as 1480, well before Columbus’s discovery of the West Indies; however, there is no concrete evidence of their presence, and the first documented exploration of the northeastern shores is John Cabot’s expedition of 1497, which resulted in his discovery of Newfoundland. The official record of subsequent sixteenth-century expeditions to North America is rather sparse, but there are two lines of evidence about the high frequency of undocumented interactions between Basque, French, and English fishermen and native inhabitants of the Northeast coast. One is the existence of a Basque-based trade pidgin, used by the Micmac Indians of the Gaspe Peninsula (Bakker 1988). The second is archeological evidence (complemented by a few contemporary observations) of European trade goods, such as glass beads and brass kettles, which began to appear sporadically after 1500 but were already fairly common at interior sites by the 1580s (Noble 2004). They occur particularly in Susquehannock graves of this period, in southeastern Pennsylvania. A Basque whalers’ camp, dating to the mid-1500s, has been excavated at Red Bay in Labrador.

In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano, financed by a Lyonnaise silk merchants’ syndicate and authorized by the king of France, sailed along the Atlantic coast from Florida to Newfoundland. On this voyage he sailed across Delaware Bay, which he named Vandoma, but he did not explore the river. Verrazzano spent less than a day in New York Bay; thinking it was a lake, he called it Santa Margarita and the surrounding lands, Angouleme. In Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, Verrazzano observed that the natives had “many sheets of worked copper which they prize more than gold” (Wroth 1970:137-40). Presumably this was European copper, already obtained from French or Basque traders by “down-the-line” exchange. Similarly, when Jacques Cartier encountered Micmac Indians in Chaleur Bay near the Gaspe Peninsula in 1534, these natives were prepared to trade their furs for hatchets, knives, and beads. Evidently, the Micmacs already knew, from previous encounters, what the Europeans craved.

Verrazzano’s (1524) account of his sojourn at Narragansett Bay contains some interesting ethnographic information.

“We frequently went five to six leagues [i.e., about 15-18 miles] into the interior, and found it as pleasant as I can possibly describe, and suitable for every kind of cultivation-grain, wine, or oil. For there the fields extend for 25 to 30 leagues [about 75-90 miles]; they are open and free of any obstacles or trees, and so fertile that any kind of seed would produce excellent crops. Then we entered the forests, which could be penetrated even by a large army; the trees there are oaks, cypresses [probably Juniperus virginiana], and others unknown in our Europe. We found Lucullian apples [cherries?], plums, and filberts [hazelnuts], and many kinds of fruit different from ours. There is an enormous number of animals-stags, deer, lynx, and other species; these people, like the others, capture them with snares and bows, which are their principal weapons. Their arrows are worked with great beauty, and they tip them not with iron but with emery, jasper, hard marble, and other sharp stones. They use the same kind of stone instead of iron for cutting trees, and make their little boats with a single log of wood, hollowed out with admirable skill; there is ample room in them for 14 to 15 men; they operate a short oar, broad at the end, with only the strength of their arms, and they go to sea without any danger, and as swiftly as they please. When we went farther inland we saw their houses, which are circular in shape, about 14 to 15 paces across, made of bent saplings; they are arranged without any architectural pattern, and are covered with cleverly worked mats of straw which protect them from wind and rain. …They move these houses from one place to another according to the richness of the site and the season. They need only carry the straw mats, and so they have new houses made in no time at all. In each house there lives a father with a very large family, for in some we saw 25 to 30 people. They live on the same food as the other people--pulse [a mistaken identification of maize kernels?] (which they produce with more systematic cultivation than the other tribes, and when sowing they observe the influence of the moon, the rising of the Pleiades, and many other customs derived from the ancients), and otherwise on game and fish” (Verrazzano 1524).

The extensive cleared lands and open forests described by Verrazzano suggest that native agriculture on the coast of southern New England was intensive and that the forest was being periodically burned to remove the understory. Sauer (1975:58) noted that the trees mentioned by Verrazzano are species that colonize old agricultural fields.

In 1525 a Portuguese pilot sailing for Spain, Estevao Gomes, sailed along the east coast. He kidnapped more than 58 natives somewhere on the coast of Maine or Newfoundland and took them to Spain where he tried to sell them as slaves (Vigneras 1957).

After these voyages, it was almost 80 years until officially sanctioned exploration of the New England coast resumed. Unlike Verrazzano, these later explorers generally sailed along the coast from the north and turned back after they reached Cape Cod. They included Bartholomew Gosnold (1602) (who rounded the cape, sailed to and named Martha’s Vineyard before turning back), Martin Pring (1603), Samuel de Champlain (1604-1605), George Weymouth (1605), and John Smith (1614). Although a few cod fishermen may have ventured into Massachusetts Bay before Gosnold’s 1602 voyage, the great majority of 16th-century fishing voyages headed farther north, to Newfoundland. English fishermen started visiting Newfoundland in the 1570s.

The first English colonization efforts on the coast of North Carolina, from 1584 to 1587, failed. They made another effort at Jamestown in 1607. In 1608 John Smith set out from Jamestown to explore the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. When he visited the Tockwoghs on the Sassafras River, Smith was surprised to discover that they already had many trade goods, “hatchets, knives, peeces of iron and brasse,” which they reportedly had obtained from the Susquehannocks (Smith 1986 (1624)).

In 1609 Henry Hudson, an Englishman financed by the Dutch East India Company, searched for the Northwest Passage to Asia. Instead, he found the Hudson River (first known as the Mauritius, then the North River). He sailed upriver as far as present-day Albany. Hudson also entered the Delaware Bay, on August 28, 1609. Robert Juet, the mate of Hudson’s ship, the Halve Maen (Half Moon), kept a journal in which he remarked that the local Indians (a branch of the Munsees) along the Hudson possessed “red Copper Tobacco pipes, and other things of Copper [which] they did wear about their neckes” (Juet 1609 [1909]:18). These seem to have been trade goods, and the Indians’ cautious behavior toward Hudson’s crew suggests that they had already had hostile encounters with other Europeans.

Dutch merchants quickly dispatched trading ships to exploit Hudson’s discovery by acquiring beaver pelts. The first venture of this sort was in 1611. Ten thousand pelts were reportedly acquired from the Hudson River Indians in the winter of 1613-1614 (Kraft 1989). A fortified trading post, Fort Nassau, was established in 1614 on Castle Island in present-day Albany, to trade with the Mohawks and their Algonquian-speaking neighbors, the Mahicans. The Dutch agents induced these warring rivals to sign a peace treaty. At about the same time the Dutch built another small fort at Esopus; and in 1615 they built a small fort on Manhattan.

Dutch explorer and fur trader Captain Adriaen Block sailed along the coast of southern New England in 1614. A 1616 map discovered in the Royal Archives in the Hague in 1841 probably was based on a map drawn in 1614 by Block (O’Callaghan 1856; Williamson 1959:8). On this map, the inhabitants of the area inland from the western Connecticut shoreline are labeled as “Makimanes.” This was not a corruption or misreading of the name “Mahicans,” because the latter are shown on the map straddling the Hudson, to the west of the Makimanes. The Makimanes appear again, closer to the shore, on Blaeu’s map of 1635. On Jansson’s 1651 map, and Nicholas Visscher’s 1655 map based upon it, a people called “Pachami” are shown farther inland. De Laet reported in 1625 that the Pachami lived on the east bank of the Hudson at Fisher’s-reach (now Fishkill). South of the Pachami, nearer the coast, Jansson and Visscher show a group called “Siwanoys.”

Block 1614

Blaeu 1635

Jansson 1651

Since the mid-19th century, some scholars have believed that “Siwanoy” was the name of the Native group that occupied the coastal areas of present Westchester County, including Rye and Harrison. The word “Siwanoy” resembles the Algonquian words for “southerner,” “wampum,” and “salty, sweet, pungent.” In the Munsee language, “southerners” was Sawanoos. Similarly, the unrelated Shawnee of Ohio called themselves shawanwa, “southerner.” The Siwanoy were thought by 19th-century scholars to be a tribe belonging to the Wappinger confederacy. However, modern researchers question the reality of both the confederacy and the supposed Siwanoy tribe (Bell 2014).

Pandemics

Reconstruction of the indigenous sociopolitical organization at the time of European contact is rendered very difficult by three factors: 1) We do not know how important maize-based agriculture was, whether this practice fostered year-round occupation of villages, whether maize sustained large populations, or whether these populations were stratified with a ruling elite of hereditary chiefs; 2) Dutch and English colonists, with their own ethnocentric assumptions about ranked political organization, dubbed local Native headmen (sakimaw or “sagamore” or “sachem”) as authoritative “chiefs” or “kings” in order to negotiate and sign deeds and treaties; 3) Face-to-face contact between colonists and Indians occurred after diseases had swept through the native peoples, causing massive population losses and social disruption.

The 1616-1619 epidemic that ravaged the natives of New England probably started in Newfoundland. That epidemic (possibly an outbreak of rat-borne leptospirosis infection) (Marr and Cathey 2010) killed as many as 90 percent of some coastal peoples and also penetrated some distance into the interior. John Smith estimated a 15-mile penetration; later writers have suggested the epidemic spread some 50 or 60 miles into the interior. A later smallpox epidemic spread up the Connecticut River valley in 1633-1634. It also hit the Mohawks in eastern New York. Native populations were dramatically reduced by successive waves of virgin-soil epidemics of European-introduced diseases; 17 epidemics are recorded in the Northeast between 1624 and 1783 (Cook 1973; Snow and Lamphear 1988). The cumulative effect of these diseases had reduced the native population of the Northeast to a small remnant by the mid-eighteenth century—perhaps 10 percent of the pre-Contact population. Perhaps the disappearance of the Makimanes and Pachami is attributable to the 1634 epidemic.

English Colonists and Indian Deeds in Rye 1660-1705

Despite the toll taken by the epidemics and by wars against the Dutch and English colonists, Native people continued to occupy the area of modern Rye and Harrison into the 1690s.

In July 1649 Megtegichkama, Oteyochque, and Wegtakochken sold a tract called “Wiequaes Keck” to Peter Stuyvesant as agent for the Directors of the Dutch West India Company (Gehring 1980). They were identified as the “rightful owners” of this land, but their sale was witnessed and approved by the chief Seyseykimus with the agreement of their friends and blood relatives. This tract extended from the North (Hudson) River to the stream called Seweyruc [Byram River]. The Indians received in exchange, 6 fathoms of duffels, 6 fathoms of seawant (wampum); 6 kettles, 6 axes; 6 adzes, 10 knives, 10 awls, 10 corals, 10 bells, 1 gun, 2 staves of lead, 2 lbs. of powder; and 2 cloth coats. The signers of the deed were Pomipahan, Meytehickhama, Wegtakachkey, and Seyseychkimus, (as witness). Although used here as a place-name, Wiequaeskeck usually occurs in colonial documents (with many different spellings, such as “Wickerscreek”) as an ethnonym referring to the Native people living between the Hudson and the Sound.

In June 1660, Indians sold part of this tract again, this time to three English colonists from Connecticut: Peter Disbrow, John Coe, Thomas Studwell. The land conveyed was Manursing Island (referred to as “Manussing, or Mennewies” in the deed). The Indian sellers were Shanasockwell, sagamore, Maowhoue (or Maowhobo) and Cokensikoe. In exchange they received eight coats and seven shirts, fifteen fathom of wampum. The deed was signed by Shanasockwek, Aranaque, Cokow, Wawatauman, Cokinseco, Maowbert, Quauaike, Aramapow, Wonanas, Topogone, Matishes, and Richard (Gehring 1980).

Peter Disbrow may have already bought Peningo Neck in January 1660, but he lost the deed, if one existed. Nevertheless, this purchase was cited in a 1720 petition by the people of Rye for a patent; the tract was said to have extended from a place called Rahoiiancss to the east as far as the Moaquanes (Mockquams) River (Blind Brook) to the west.

In May 1661, a group of Indians including some individuals from the June 1660 deed (Cokoe [Cokow], Marrmeokhung, Assawarwone, Nahtimeman, Shocote, and Wauwhowarnt) sold to Disbrow a tract on the mainland, stretching between Byram River and Blind Brook.

On November 8, 1661, Cokeo, Shanarocke, Rawmaquaie and Cockenseco sold to John Budd of Southold a tract in present-day Rye, bounded on the east by Blind Brook and on the west by the Pockcotessewake River, now Beaver Swamp Brook. This tract stretched "northward as far as Westchester Path, and southward to the sea." What appears to be a different version of this deed, also dated November 8, was signed by Shanarocke, sagamore, and Rackceat, Mapockheast, Tawwheare, Nanderwhere, Tomepawcon, Rawmaguaie, Pawaytahem, Mawmawyton, Howhoranes, Cockkeneneco, Taroewayco, Attoemacke, and Heattomeas (Gehring 1980).

On November 12, 1661, Shenorock, Rawmaqua, Rackeatt, Pawwaytahan, Mawmatoe, and Hownis sold to Budd the “West Neck,” adjacent to the neck he had already purchased. The West Neck lay between Stony Brook and the “Merremack” (Mamaroneck) River. The sellers received coats and 60 fathom of wampum.

On November 5, 1661, Budd bought from Shenerock, sachem (i.e., Shanarocke), Hen and Pine Islands and the Scotch Capes (“the islands lying south from the neck of land the sayd John Budd bought of me and other Ingains”).

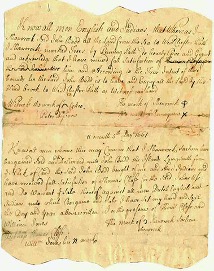

1661 deed of islands from Shenerock to John Budd

In June 1662, a tract adjacent to Budd’s was sold to Peter Disbrow, John Coe, Thomas Studwell, and John Budd, by Showannowocot, Roksohtohkow and Pewahaham and other Indians.

In a document dated April 29, 1666, Shonarocke Sagemore, Romackqua and Pathung reaffirmed the November 8, 1661 sale to John Budd, clarifying that the land stretching inland, called Apawamis, extended 16 miles beyond the Westchester Path (later known as the Boston Post Road). This document was signed by Shonarocke, Cokoe, Romackqua (“a sachem’s son”), and Pathung (Gehring 1980).

In September 1680, an Indian named Maramaking, known to the English as Lame Will, sold to the Proprietors of Peningo Neck (represented by Robert Bloomer, Haccaliah Brown and Thomas Merit) a tract beside Blind Brook. The Indians called this area Eaukecaupacuson and the English called it Hog Pen Ridge. The deed was signed by Couko, Maramaking, and Owrowwoahak. Maramaking was probably “Marrmeokhung” who signed the May 1661 deed. Given the vagaries of transliteration and spelling, Owrowwoahak could have been the sachem’s son, Romackqua (Rawmaquaie), who signed the 1661 deed. Apparently there was some confusion about the 1680 sale, because the deal was renegotiated and another deed was signed on October 8, 1681. This time it was signed by Maramaking, Wessaconow, Cowwows, and Pummetum (probably Pawwaytahan, Pawaytahem of the earlier documents) (Gehring 1980).

In February 1695, Pathungo confirmed the sale, to John Harrison of Long Island, of a tract (adjoining Budd’s land) from Mamaroneck River to Blind Brook. Pathungo was presumably the same “Pathung” who had signed the 1666 document. However, Pathungo reserved for his own use “such white-wood trees [probably tulips] as shall be found suitable to make canoes of.” It is noteworthy that most of the Indian signers (except Pathungo Wappatoe, Porige, and Arowash/Arawaska/Akabaska) were women:

- Betty Pathungo

- Pathungo Wappatoe

- Elias Jozes Pathungo Askamme [Pathungo’s wife]

- Chrishoam Pathungo [a woman]

- Porige

- Elaas Arowash, Arawaska’s wife, Hannah

- Akabaska

The last reported sale by the local Native people is Pathungo’s sale of Rye Pond in 1705.

A great-grandson of John Budd sold the site of the Jay estate to Peter Jay in 1745.

Ninteeenth-century historians pointed to several places in Rye as the former sites of indigenous occupation.

Bolton (1848) observed that, “The former existence of Indian habitations on the great neck of Poningoe is amply proved by the number of hunting and warlike weapons found in that neighborhood. The site of the principal Mohegan village was on or near Parsonage Point. In the same vicinity is situated “Burying Hill,” their place of sepulture. The remains of six Indians were discovered on excavating the present foundations for Newberry Halstead's residence, which stands near the entrance of the great neck [west of Rye Beach].”

Baird (1871) surmised that the first English colonists in the area had been drawn to Peningo Neck and Manursing Island because the Indians had already cleared the land there for cultivation. He noted “the abundance of Indian remains in this neighborhood.”

Ruttenber (1872) stated that “A very large village of the chieftaincy was situated on Rye Pond in the town of Rye. In the southern angle of that town, on a beautiful hill now known as Mount Misery, stood one of their castles. Another village was situated on Davenport’s Neck.”